Battery thermal runaway: how it starts & how it’s prevented

Lithium-ion batteries power much of modern life — from phones and laptops to e-bikes and home energy storage systems. When incidents occur, they often attract disproportionate attention, producing sensational headlines about batteries “self-combusting” or “exploding.” In reality, lithium-ion batteries do not ignite spontaneously. Fires happen very rarely, and only when a specific chain of technical failures means heat builds up faster than it can be removed, which eventually triggers thermal runaway.

This blog post provides a simplified, engineering-led background of lithium-ion battery thermal runaway, paying particular attention to:

The building blocks of lithium-ion cells

How failures develop in real-world systems and the steps that can lead to thermal runaway

Why battery chemistry matters for safety

How robust system design and monitoring are important for long-term operation

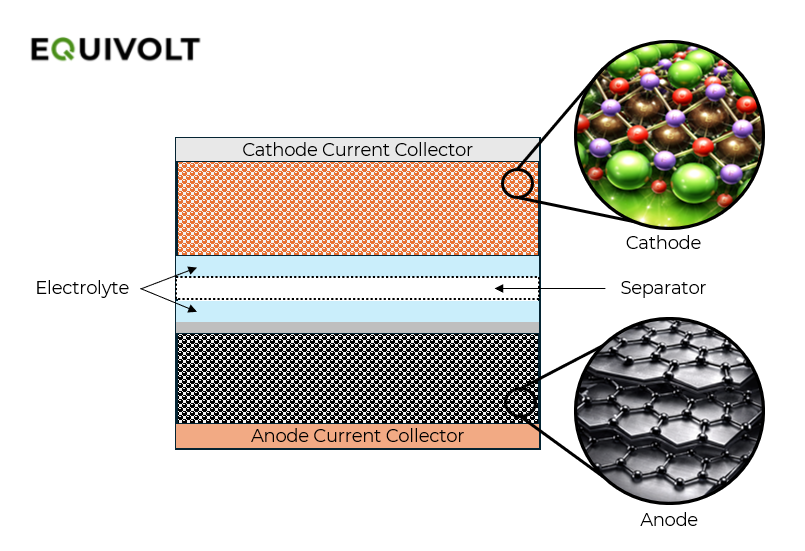

What’s inside a lithium-ion cell?

Batteries are made of collections of cells and an individual lithium-ion cell is a tightly packed “sandwich” made up of five key elements:

Anode: usually graphite as the active material

Cathode: chemistry dependent - e.g., LFP, NMC, NCA

Separator: a porous polymer film preventing contact of the anode and cathode

Electrolyte: typically an organic solvent & lithium salt

Current Collectors: Metal sheets attached to the anode and cathode

Figure 1 - Simplified Cell Overview

During charging, an external power source pushes lithium ions out of the cathode and into the anode, “parking” them there and storing electrical energy. This process is known as intercalation of lithium ions and can be visualised like stacking books (the Li ions) neatly onto a bookshelf (the anode, during the charging phase). During discharge, the lithium ions travel in the opposite direction back toward the cathode, reversing the intercalation process and releasing the previously stored electrical energy for use.

Lithium-ion cells hold a lot of energy in compact, reactive materials, so safety is vital. The main priorities are stopping situations that cause overheating or internal shorts, and building systems that detect, isolate, and contain faults before they spread to prevent thermal runaway.

How lithium-ion batteries fail

Almost all serious lithium-ion battery fires begin with an internal short circuit, caused by one or more of the following:

1) Manufacturing defects

Rare but real. A tiny metal particle, a burr, misalignment, or contamination can create a latent defect that only becomes a problem after months or years of cycling. Industry reviews of battery defects consistently highlight how impurities (for example, stray metal particles) can lead to internal shorts, degraded performance, and serious safety risks. That’s why quality control matters: reputable manufacturers and pack assemblers perform thorough incoming inspection, careful cell matching, strict process controls, and rigorous testing designed to catch these issues early in the production cycle. At EquiVolt, every battery system uses batch-tested cells sourced from regulated, approved suppliers.

2) Mechanical abuse from damage, crushing, vibration or poor installation

If the separator is torn, folded, or otherwise compromised, the electrodes can come into contact and cause an internal short circuit. In a home system, prevention focuses primarily on a few key measures: careful siting - choose a location that is well away from vehicle movements or provide robust impact protection; secure, level mounting to minimize the risk of knocks, vibration, or shifting that could disturb internal components; correct support and routing of auxiliary systems so they do not place stress on the battery internals; and using only battery enclosures and cases that meet the requirements of PAS 63100:2024.

3) Electrical abuse

Overcharging pushes the cell into unstable chemical and electrical states and produces internal heat. Protection systems are engineered specifically to prevent this from happening - but they must be correctly configured, regularly maintained, and never bypassed or tampered with.

Battery Management Systems (BMS) and cell balancing together provide essential safeguards that significantly reduce the risk of electrical abuse and thermal runaway. All EquiVolt systems include multiple layers of protection, including remote monitoring, an integrated BMS, inverter limits, active cell balancing, and hard-coded safety settings to ensure reliable, long-term operation.

4) Ageing & cold charging

Lithium plating is a significant cause of battery damage: charging at very low temperatures (lower than −10 °C) or charging too quickly can leave metallic lithium on the anode. Those deposits can grow into dendrites that cause internal shorts and cell failure. Studies on thermal runaway and fast charging identify low‑temperature rapid charging as a major risk for plating and related safety problems.

This is one reason stationary systems are deliberately conservative: they favour controlled charge rates and temperature-aware limits rather than a “fast at any cost” approach. That important distinction is a major difference between the challenges posed to Electric Vehicles (EVs) and static storage systems. EVs require the flexibility to charge and discharge very quickly to keep you on the road. EquiVolt static storage systems, by contrast, are designed to trickle charge and discharge, massively extending battery life and reducing stress on the cells while prioritising long-term reliability and safety.

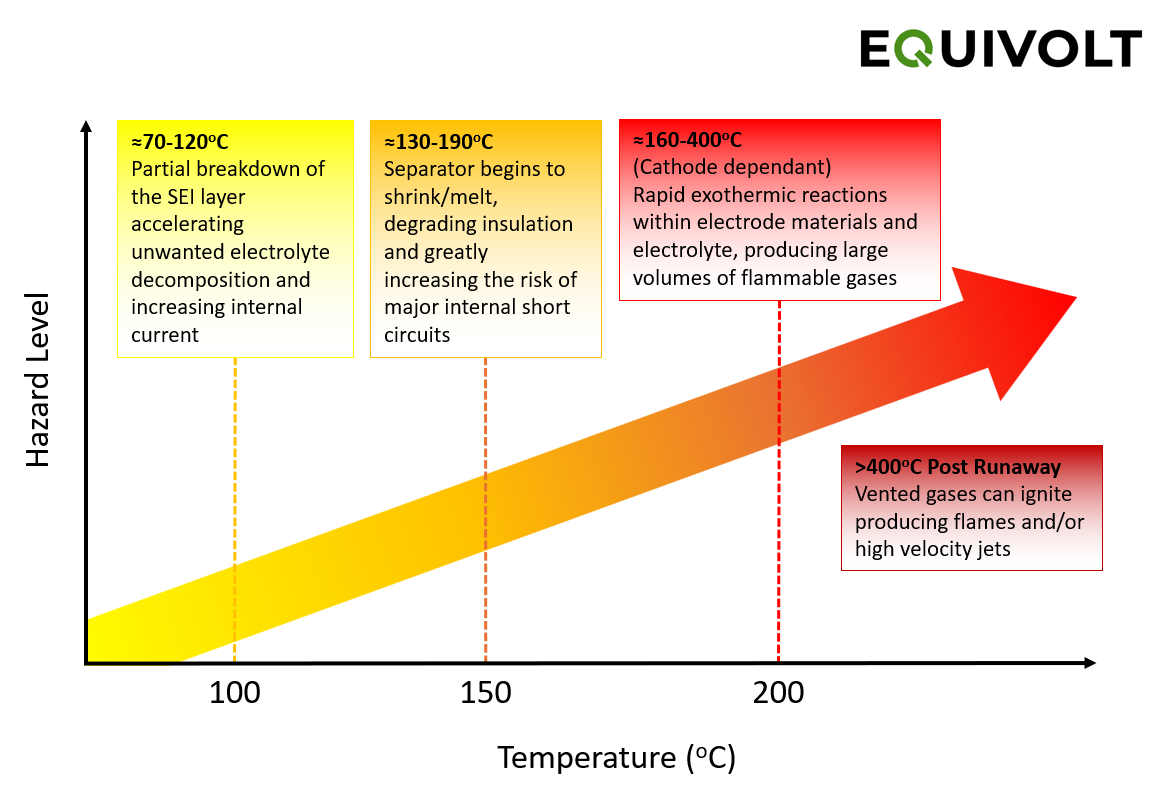

Thermal runaway is a cascade, not a single event

Once an internal short forms, heat generation can exceed heat dissipation. A typical progression looks like this:

Figure 2 - Thermal Runaway Stages in Lithium-ion Cells

Why battery chemistry matters for thermal runaway

Battery chemistry strongly influences several safety and performance factors: the temperature at which thermal runaway begins, the rate and intensity of heat release during that event, the likelihood of oxygen being released from the cell’s internal structure, and the severity of gas generation and flame propagation. This is precisely where Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) differs fundamentally from many other lithium‑ion cathode chemistries, such as NMC and NCA, offering distinct thermal stability and lower propensity for violent oxygen-driven reactions.

LFP vs other chemistries

Layered metal-oxide cathodes (LCO, NMC, NCA) are used widely in phones, laptops, power tools and electric vehicles. These chemistries offer high energy density and strong performance in compact formats. However, their cathode structures can release oxygen at elevated temperatures, and that released oxygen can sustain combustion even when external air is limited. They generally have lower thermal runaway onset temperatures than lithium-iron-phosphate chemistries and runaway events from them can be more energetic. With careful engineering, appropriate controls and protective measures they are safe in normal use, but they are less forgiving under severe abuse or failure conditions.

LFP is widely regarded as the best choice for UK home battery systems due to its balance of safety, longevity and cost-effectiveness.

Key safety advantages:

Strong phosphate bonding

The phosphate (PO₄³⁻) framework tightly binds oxygen atoms, making oxygen release during overheating far less likely. That chemical stability reduces the cathode’s ability to feed a fire and lowers the risk of violent reactions under fault conditions.Higher thermal stability

Comparative abuse testing consistently shows that LFP cells have higher thermal runaway onset temperatures than many nickel- or cobalt-based chemistries, giving a significantly greater safety margin in the event of abuse, overheating or external heat exposure.Lower runaway severity

While LFP cells can still burn in extreme circumstances, they typically exhibit lower peak heat release and much slower propagation of thermal events compared with layered oxide chemistries of similar format and state of charge, reducing the likelihood of cascading cell failures.More stable ageing behaviour

LFP chemistry is less prone to oxygen-driven degradation mechanisms and tolerates very high cycle counts without destabilising internal structures. That means not only a safer battery but also a longer useful lifespan and better long-term performance.

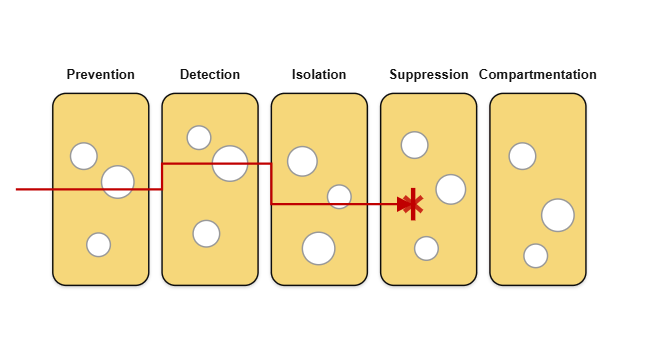

Robust system design and monitoring are critical to long-term safe operation

A useful way to think about battery safety is as a series of layers: each protection layer adds additional safeguards and redundancy. No single layer is ever 100% guaranteed, so using multiple layers increases the chance of detecting, containing, and stopping any malfunction before it can escalate into a dangerous situation.

This visualisation is called the "Swiss cheese" approach: each safety layer is a slice of Swiss cheese with holes. An accident only happens if the holes line up through all the layers. Since no layer is perfect, the goal is to keep the holes from aligning.

Figure 3 - ‘Swiss Cheese Model’ of protection layers

1) Prevention: avoid the trigger

Goal: don’t let the battery cells enter abusive conditions in the first place.

Chemistry choice: LFP for higher thermal stability margin, as discussed above.

Quality cells & batch screening: reject outliers by testing for capacity, internal resistance and self-discharge.

Conservative operating limits: don’t run cells at the edge of voltage/current/temperature capabilities.

Good mechanical design: no rubbing, crushing, loose busbars, or sharp edges that can damage separators.

Right-sized inverter vs battery: current limits that respect what the battery can safely deliver.

2) Detection: spot abnormal behaviour early

Goal: catch the “first step on the staircase” before it becomes a runaway chain.

Per-cell voltage monitoring: detect drift, over-voltage risk, weak cells.

Temperature sensing: at cell/module level and on critical conductors such as busbars and cables.

Current sensing: detect abnormal charge/discharge, unexpected spikes, or sustained high current.

Trend monitoring: increasing imbalance, unusual temperature rise at the same power.

Remote health checks/telemetry: frequent monitoring to flag early anomalies and extend battery life. EquiVolt+ remotely monitors our battery systems to detect anomalies and maximise longevity.

3) Isolation: stop energy flow

Goal: physically interrupt the energy path so heat generation can’t keep escalating.

BMS-controlled current contacts: open the battery circuit when current, temperature or resistance limits are exceeded.

Fuses/DC circuit breakers: hard protection if a fault causes extreme current.

Inverter shutdown: stop charge/discharge immediately on detecting any battery faults.

DC & AC isolators for maintenance/emergency: a clear, reliable way to disconnect safely.

4) Suppression: control fire/heat

Goal: if something gets past the first three layers, reduce heat and flame intensity.

Integrated aerosol/clean-agent suppression inside the cabinet: provides “belt and braces” security.

Thermal barriers/insulation: slow heat transfer to neighbouring modules.

5) Compartmentation: prevent spread

Goal: assume a single cell could fail, and design so it doesn’t take the whole pack with it.

Cell/module spacing: reduces direct heat transfer.

Fire-resistant barriers between groups of cells/modules: slows propagation.

Propagation-resistant pack architecture: smaller “sections” rather than one big thermal mass.

Defined vent paths: so a failing cell vents outward rather than into neighbouring cells.

Mounting and siting choices: keep the system out of escape routes and away from combustibles, with sensible clearances.

How EquiVolt apply these ideas

High-quality battery packs

Our battery packs use LFP cells with built in BMS, cell balancing, heating, and fire suppression. The Fogstar Energy ECO 16.1 kWh 51.2 V battery EquiVolt currently use is an LFP cabinet battery built around a 16-series configuration, typical for “48 V class” systems. It’s specified with:

Grade A 314 Ah cells in a 16S1P arrangement,

a 200 A BMS,

a JK 2A active balancer,

built-in heating (supporting charging in cold conditions),

and integrated heat-activated aerosol fire suppression.

Each of those matters:

BMS prevents over/under-voltage and over-current conditions from silently developing into abuse.

Active balancing keeps cell voltages aligned, more on why that’s important below.

Heating reduces cold-charging risk, which is one of the root causes behind lithium plating concerns discussed earlier.

Integrated suppression is a “belt and braces” layer: it’s not there because we expect failure, it’s there to stop a very unlikely event becoming a dangerous one.

Inverter: current limiters, remote monitoring & grid protection

The Afore 3.6kW-SL single-phase hybrid inverter used in EquiVolt systems:

Provides a maximum battery charge/discharge current of 80 A, well below the 200 A supported by the battery. This naturally limits how hard the battery can be pushed in normal operation meaning less stress, less heat and a longer battery life.

Provides protection features including anti-islanding, short-circuit protection, residual current detection, ground fault monitoring, PV arc detection, and surge protection Type II.

The inverter is also G98/G100 certified, which means an independent third party has documented and verified all required tests.

The EquiVolt+ Controller is the remote brain of the system, monitoring and catching any abnormalities before they can develop into a concern.

Cell balancing is a bigger deal than most people think

A 48 V LFP cabinet is typically 16 cells in series. In series strings:

Current is the same through every cell, but cell voltages can drift slightly over time because no two cells are identical.

If one cell drifts higher during charge, it can hit a voltage limit sooner than the rest, which is why a proper BMS & balancing strategy matters:

Balancing reduces drift

The BMS watches each cell voltage and if anything looks wrong, it can stop charge/discharge before a weak cell is abused.

This is also where quality control feeds into safety: matched cells with similar capacity/internal resistance are easier to keep in line.

Professional install & commissioning

A great battery and a great inverter can still be made unsafe by poor installation. Commissioning is where the system proves it behaves as designed.

EquiVolt’s robust commissioning process includes:

Verifying correct protective device performance

Confirming BMS/inverter communications and correct battery profile

Testing charge/discharge under supervision

Confirming remote monitoring, alerts, and shutdown behaviour

Clearly labelling all equipment and providing user handover.

All of these points align with UK best practice (PAS 63100) and the broader framework of EESS safety standards.

Final thought

Lithium-ion batteries are neither uniquely dangerous nor risk-free. They are energy-dense electrochemical systems, and safety depends on chemistry, engineering, quality control, and how they are used.

LFP does not make batteries invincible, but it meaningfully improves thermal stability and failure tolerance, which is why it has become the preferred chemistry for many UK home energy storage applications and the exclusive choice for all EquiVolt storage systems.